|

| Srinivasa Ramanujan |

The anniversary comes at a tragic time for

India. Sectarian and police violence have claimed many lives, mostly Muslim,

following the passing of a discriminatory Citizenship Amendment Act in 2019

aggressively promoted by Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Hindu-Nationalist

Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Indians of all faiths have been demonstrating

against the law, although the coronavirus contagion has halted it for now. (But

the pandemic has added its own macabre twist to the story. Reports are now

emerging that right-wing fanatics are attacking and killing Indian Muslims for

spreading the virus!) The

original Citizenship Act of 1955 guaranteed citizenship to every Indian

irrespective of religion, reflecting the aspirations of a secular, democratic nation.

The amended bill favors all major religions of South Asia except Islam, a

blatant discrimination against India’s 200-million Muslim community.

Remembering Ramanujan against today’s India

offers lessons about the insidious ways by which bigotry and injustice can

erode the soul of a nation and stifle the flowering of its geniuses.

Ramanujan would have

withered away as a shipping clerk in Madras (now Chennai) had it not been for

the patronage of an Englishman. In 1913, the same year that Rabindranath

Tagore, another son of India, won the Nobel Prize for Literature, Ramanujan

wrote a letter to the Cambridge mathematician G. H. Hardy to rescue him from

oblivion. Trying to digest the 50 or so theorems included in the letter, Hardy

realized he was dealing with a rare phenomenon. The mathematics seemed so

sublime that Hardy was convinced “the results must be true, because, if they

were not true, no one would have the imagination to invent them.”

|

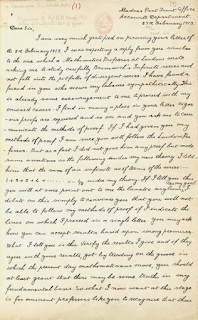

| Ramanujan's Letter to Hardy |

|

| G.H. Hardy |

Hardy managed to

bring Ramanujan to England through a grant, giving him an intellectual home at

Cambridge where he flourished for five years, producing pioneering work in such

branches as number theory and partition function that secured his reputation as

among the greats of mathematics. The serendipitous discovery of Ramanujan’s

“Lost Notebook” by Wisconsin University Mathematics professor George Andrew in

1976 that included calculations involving “mock theta functions,” 56 years

after he worked them out in India, has added to the enigma and the otherworldly

genius of Ramanujan. The late physicist Freeman Dyson (1923-2020) aptly summed

up Ramanujan’s achievement: “That was the wonderful thing about Ramanujan. He

discovered so much, and yet he left so much more in his garden for other people

to discover … I have intermittently been coming back to Ramanujan’s garden.

Every time I come back, I find fresh flowers blooming.”

|

| From Ramanujan's Notebooks |

Ramanujan’s theorems are

now applied in fields ranging from particle physics and statistics to cryptology

and computer science. His approximation for pi, the ratio of a circle’s

circumference to its diameter, finds use in today’s fastest algorithms in computing

the irrational number to trillion decimal places.

Ramanujan was lucky. (So was Tagore. Had not

the Irish poet Yeats championed his work in the West, the Bengali poet would

unlikely to have won the Nobel.) But for every Ramanujan who succeeded, how

many Ramanujans must have died on the vine when the British ruled the

Subcontinent for over a century? Colonial powers by their nature subjugate,

exploit and massacre. But when the oppressors are one’s own leaders, what’s the

excuse? Modi and his BJP passed the Citizenship Act to marginalize Muslims or

drive them out of India. Such overt discrimination affects not only the target population

but the entire nation, preventing potential Tagores and Ramanujans from ever seeing

the light of day.

The human potential of India is incalculable. We

get a sense of it by the disproportionate number of Indian American engineers

and CEOs keeping hi-tech companies humming right here in Silicon Valley. Brain

drain from India and other countries will continue so long as the West offers better

opportunities to immigrants. While India cannot provide such opportunities for

all, passing discriminatory laws against a segment of its population diminishes

the nation and shackles its geniuses, be they Hindu, Sikh, Christian or Muslim.

When a government becomes tyrannical, the creative vitality of its

people seeps away as from cut flowers in a vase.

No comments:

Post a Comment